The hole in the ozone layer, which was discovered almost 40 years ago, may not be recovering as quickly as projected, according to a new study.

The implications of the paper are being debated by other scientists as the research questions well-established views on ozone recovery.

Since ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were banned from manufacturing in 1987, it's been thought the ozone layer — which sits between 15 and 30 kilometres above Antarctica — has been slowly but surely bouncing back.

But in a study in Nature Communications, researchers from the University of Otago suggest the hole's repair isn't as pronounced as we thought, and the swirling mass of cold air around the South Pole might be involved in its delayed recovery.

"That's something that's not thoroughly understood yet, and we have more work to do to understand the mechanism," study lead author and PhD student Hannah Kessenich said.

"I think if we're projecting a timeline of recovery it's important to know all the key players impacting the ozone hole today."

A decade before the hole was confirmed in the 1980s, scientists discovered chemicals used in aerosols and fridges could deplete Earth's ozone layer, which protects us from the Sun's harmful ultraviolet radiation.

CFCs in the atmosphere influenced the annual thinning of ozone over Antarctica, which can have major impacts on weather in the southern hemisphere.

The hole, which grows in August every year before shrinking again in December, can modify wind and rain patterns and contribute to drier conditions in places like Australia.

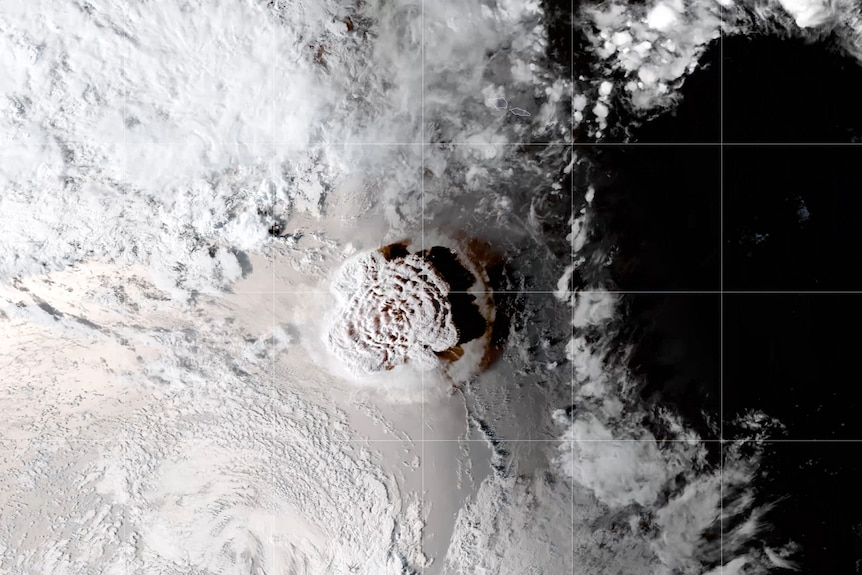

Major fires and volcanic eruptions have contributed to larger-than-usual "ozone holes" over Antarctica in recent years.

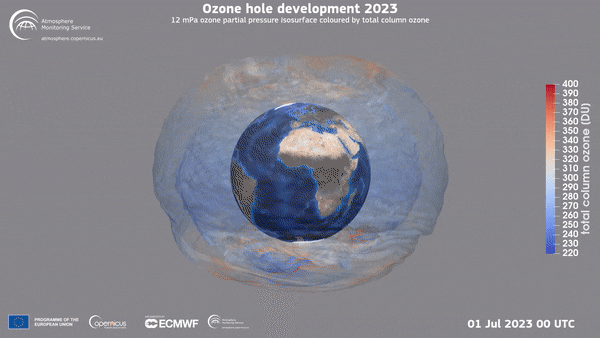

This year the hole reached 26 million square kilometres in size, about 3.4 times the land area of Australia.

The ozone layer above Antarctica is expected to recover to pre-1980s levels by 2066.

But the new research suggests that recovery trends are not as clear cut when looking at what's called "total column ozone" — all the ozone in the atmosphere above a select point on Earth — over the past two decades.

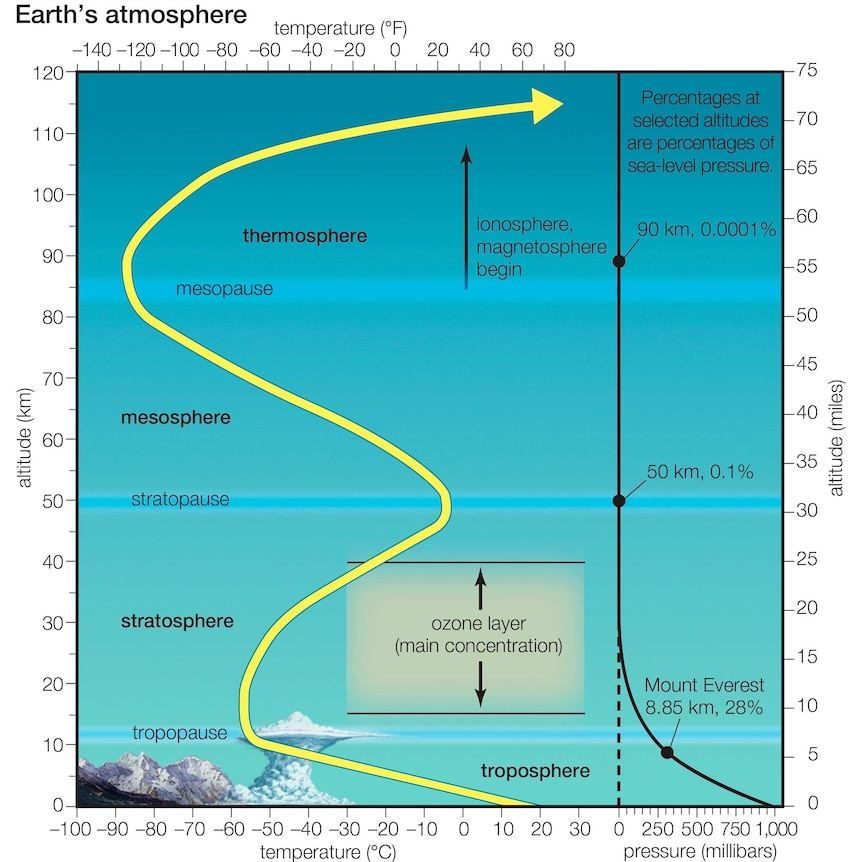

The ozone layer is found in the stratosphere, about 15 to 30 kilometres above the surface.(Getty Images: Encyclopedia Britannica)

For instance, Ms Kessenich said there was less ozone around the core of the hole which hovers near the South Pole.

The core is in the middle of the stratosphere, a layer of Earth's atmosphere found about 10 to 50 kilometres above the ground.

"If you separate out by altitude, we see there are regions where the ozone is recovering over Antarctica and regions it is not," Ms Kessenich said.

She said there appeared to be ozone recovery in the upper stratosphere and in some of the lower stratosphere around September, but that "we see at high latitudes, more towards the pole, there is a large region in the middle stratosphere where the ozone is declining".

A render of the ozone hole over Antarctica in 2023.(Supplied: Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service)

They calculated the ozone around the hole's core dropped by more than 26 per cent since 2004.

This drop was linked to changes in the mesosphere — the atmospheric layer above the stratosphere — when it descends into the area of rotating cold air around the South Pole called the polar vortex.

University of NSW atmospheric scientist Martin Jucker, who was not involved in the paper, questioned the study's conclusions.

He said the results relied heavily on the large ozone holes from the past three years.

"Existing literature has already found reasons for these large ozone holes," he said.

"Smoke from the 2019 bushfires and a volcanic eruption, as well as a general relationship between the polar stratosphere and El Niño Southern Oscillation.

"We know that during La Niña years, the polar vortex in the stratosphere tends to be stronger and colder than usual, which means that ozone concentrations will also be lower during those years."

The eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano last year is thought to have impacted the Antarctic ozone hole.(Supplied: NASA)

Dr Jucker said the study also didn't include data from 2002 and 2019 when there were so-called stratospheric sudden warmings.

Stratospheric sudden warming is a phenomenon more common in the northern hemisphere. It's caused by waves in the atmosphere, called planetary waves, which move cool air towards the equator and warm air to polar regions.

"Those events have been shown to have strongly decreased the ozone hole size, so including those events would probably have nullified any long-term negative trend in ozone concentrations," Dr Jucker said.

Data from NASA's Aura satellite was used for the University of Otago study.(Supplied: NASA)

But University of Leeds atmospheric scientist Martyn Chipperfield, who was also not part of the research, said the paper showed changes in atmospheric dynamics may affect Antarctic ozone.

"The atmosphere is a complex system and many factors can lead to changes in the thickness of the ozone layer," he said.

"We need to remain vigilant on ... [ozone-depleting] compounds but, as the paper shows, also be aware of the impact of other factors such as climate change."

Professor Chipperfield also noted the research used an instrument on NASA satellite Aura which would be decommissioned in coming years without a plan for replacement.

"Without a suitable replacement we will lose the ability to detect and understand processes such as this," he said.